The Equine Lymphatic System and Treatment of Equine Chronic Progressive Lymphoedema (CPL) by Rebecka Blenntoft - European Seminar in Equine Lymph Drainage (ESEL)

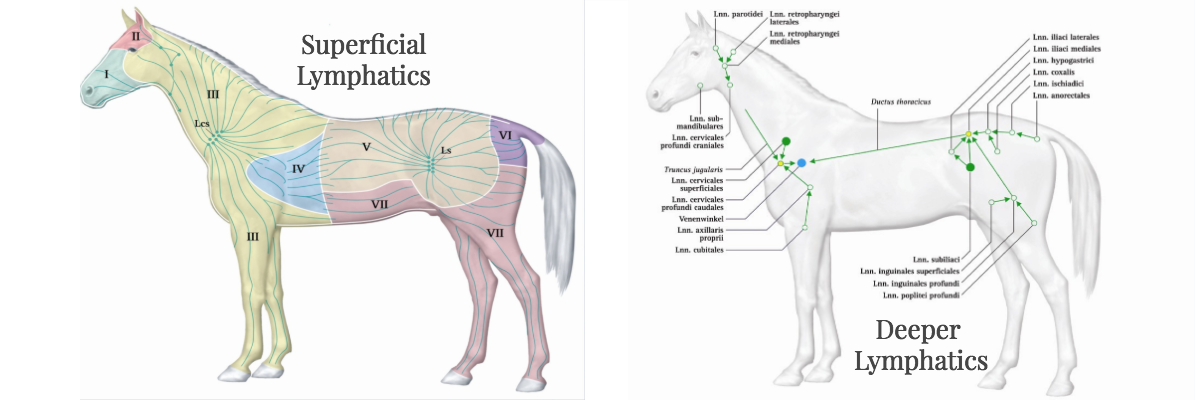

Of all the horse’s biomechanical systems, perhaps one that is least understood or looked at is the lymphatic system. Much of our current research on equine lymphology has been conducted at the Veterinary University at Hannover in Germany, where they have discovered significant differences between the equine lymphatic system and that of the humans, and this has profound implications on the way we need to look at and treat lymphatic problems as well as how we keep and manage horses on a daily basis.

"Photo Credit D Von Rautenfeld"

The lymphatic system is an extensive system of vessels and nodes that transports lymphatic fluid around the body. If you imagine that all the cells and tissues of a horse’s body are surrounded by a watery gel-like substance called interstitial fluid, and this provides a medium for dissolved oxygen and nutrients to travel across to the cells so they get all the energy they require to carry out all their metabolic processes. As well as being responsible for giving cells the oxygen and nutrients they need, the interstitial fluid transports salts, hormones, neurotransmitters, co-enzymes, amino acids, sugars and fatty acids around the body. The cells also get rid of all their waste products into the interstitial fluid, which can include cell debris, bacteria, dead blood cells, pathogens, toxins, lactic acids and protein molecules.

The health of the interstitial fluid, therefore, is fundamental to both the health of the cells and the fluid balance within the body. If too much fluid is left in the interstitium, a swelling (or oedema) occurs.

Interstitial fluid is formed from the arterial blood being pushed out into the tissue spaces (except red blood cells, platelets and plasma proteins, which stay in the blood as they cannot pass through the capillary wall). The two systems that take the excess fluid away to keep the interstitial fluid in perfect balance are the veins and the lymphatic system. The veins take away deoxygenated blood and the lymphatic system takes away the larger particles – the long chain fatty acids, protein molecules and cellular waste as these require specialised filtering.

The lymphatic system is quite a multi-faceted system - it transports the lymph around the body in very specific one-way vessels, it is involved in immune system response, it maintains the volume of the blood, maintains the health of the interstitium and connective tissue, maintains fluid balance within the body and is responsible for protein circulation.

The lymphatic system is also quite adaptable, up to a point. Lymph nodes can regenerate if there is a blood and nerve supply left to them, and lymph vessels that have been damaged can try to join onto another functioning lymph vessel, or even try to join onto a vein.

Differences between human and equine lymphatic systems

Although there are similarities between human and equine lymphatic systems, there are some significant differences between them, the misunderstanding of which can lead to the health of the horse being compromised. We must remember that the horse has evolved from a small flight animal designed to be in almost constant motion, to the animals we utilise today. Although there have been great changes in the external appearance of the horse, its physiology remains largely similar to that of its earlier ancestors and it is unlikely that the structure and the functional capacity of the lymphatic systems have changed a great deal. One study of feral populations of horses have shown them to be walking between 6 to 8 kilometres (3.5 to 5 miles) per 16 hour day, although it must be understood that if food is limited or scare, horses can travel 30 kilometres (18 miles) a day. Modern methods of keeping horses stabled, with limited time for free exercise and concentrated physical training sessions can lead to compromised lymphatics and its associated complications, namely infection and scar tissue (fibrosis).

One of the main differences in the equine lymphatic system is the difference in the structure of the lymphatic collector vessels. Horses have a significantly lower number of smooth muscle cells that make up the walls of the collector vessels. Research has revealed that equine collectors in the cutis of the skin are made from about 40% elastic fibres – much more than in humans, where the collectors are made of more smooth muscle fibre. The cutis represents the horses own “compressive bandage”, as it stiffens and exerts force when mobile. You can think of this like a corset that gets tighter when you breathe in heavily and looser when you breathe out – the extra pressure generated when you breathe in helps to compress the lymphatic vessels and gives them a bit more support. This means that the horse requires far more physical movement to activate its lymphatic retraction apparatus and encourage the transport of lymphatic fluid. These elastic fibres are assisted by a “pump mechanism” in the hoof and the fetlock joint, which assist lymph travel up the collector vessels. This high proportion of elastic fibres may have developed because there are no muscles in the lower limbs of the horse to aid with the contraction of the vessels.

Therefore, when a horse is standing still, the transport capacity of the lymphatic system decreases significantly. The rate of lymph flow travelling around the lymphatic system will be reduced and amount of lymph taken around the body will also drop. This puts the standing horse at a distinct disadvantage when recovery from injury or exertion.

In addition, the horse has an extremely high number of lymph nodes – roughly 8,000 -compared to an average of 600 in the human. As lymph slows down and concentrates upon entering each node, equines have a greater propensity for lymphatic ‘bottlenecks” than other mammals.

Many horses restricted to being stabled will suffer from “stable fill”, or swollen legs. When they start to walk again, the lymphatic retraction process normalises, and lymph starts to move out of the limb. As swollen legs in horses are generally not considered to be a disease per se, many owners will try to reduce swelling by using stable bandages over some form of padding. However, what really happens is that the swelling is pushed through the superficial lymphatic vessels to higher up the leg and gives the illusion of having dispersed.

In 2006 a large veterinary study was undertaken to examine the effect of different types of bandaging on the lymphatic vessels of the lower leg. This involved injecting a continuous stream of dye into the lymphatic vessels of horses under sedation and x-raying the effects. Horses bandaged with the elasticated bandages were found to have significantly impeded lymph flow, compared to those bandaged with specially designed compression bandages. This is due to there being no muscles below the knee and hock to provide protection to these vessels and they end up being squeezed to such a point that they can no longer function properly. Horses’ tendons have been shown to contain a high density of lymphatic vessels as compared to blood vessels, so it is vital that these are not constricted. This highlights the need for further increased awareness of the clinical effects of bandaging on lymphatic performance. The authors of the study recommended that in the future, the materials and construction of both veterinary and equine sports bandages be reconsidered, due to the detrimental effect that elasticated bandages have on the deep lymphatic vessels.

What happens when the lymphatic system is compromised?

Lymphoedema is generally not painful, nor hot to the touch. It usually presents asymmetrically, so even though both limbs may be affected, one will be worse than the other. When lymphoedema first appears, it is soft. Over time, the protein molecules that the lymphatic system should be taking away accumulate in the interstitium, which becomes more congested. The protein starts to change molecular structure so the body cannot recognise its own protein anymore and starts attacking it, leading to it getting harder and developing into what we call protein fibrosis. Once this appears it is impossible to remove, but there are techniques to improve or soften it. The interstitial fluid in that area now starts to deteriorate from optimum - collagen and elastin starts to become stiffer and dissolved oxygen and nutrients cannot be delivered to the cells so effectively. The cells cannot get rid of their waste material so effectively so the whole oedematous area becomes more and more compromised. If the oedematous area gets injured in any way, it is very likely for the horse to develop an infection (such as lymphangitis, which is an infection of the lymph vessels). When oedema is present wounds take much longer to heal and are much more difficult to heal properly.

In horses, cases of primary lymphoedema (the horse is born with a poorly developed lymphatic system) is seen more commonly in the heavier breeds such as Shires, Warmbloods, Cobs and Friesians. The most common causes of secondary lymphoedema in horses are from wounds (wire cuts, burns, lacerations, etc) or infection (cellulitis or lymphangitis). However, horses showing regular signs of stable fill, which go down on exercise, are really exhibiting the early, reversible stage of secondary lymphoedema. Over time, small microscopic changes occur to the interstitium, and the horse ends up with compromised cellular immunity in the lower legs. Therefore, some horses will develop recurrent infections, which become more difficult to manage due to the damage caused by each infection. Horses suffering in this manner are sadly often euthanised.

It is important to remember that lymphatic disease is a dynamic condition, which means it is always changing. The age of the horse, other medical factors, the amount of free exercise vs being stabled it has, and the degree to which the lymphatic system has been damaged over time will mean that no horse will ever present exactly the same, nor will they deteriorate at the same rate.

Treatment

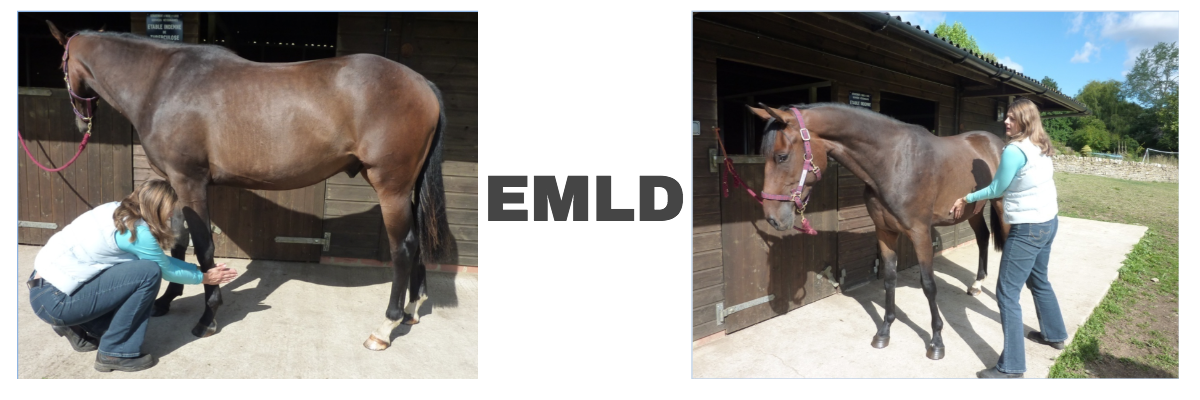

Equine Manual Lymphatic Drainage (EMLD)

As there are no drug therapies or surgical procedures available to horses for the repair of the lymphatic system, lymphoedema is considered a degenerative condition that will worsen with time. Equine Manual Lymph Drainage is the only treatment available once the lymphatics are compromised to the point of long-standing oedema. Fortunately, it can be effective and long-term prognosis can improve for horses if the oedema can be reduced and maintained, especially if the disease is caught early. Horses are excellent subjects for EMLD, responding far more effectively than humans. As there is no muscle below the knee or hock it is possible to stimulate both the superficial and deep collectors, whereas humans, it is much more difficult to stimulate the deep collectors due to a much thicker subcutaneous layer.

EMLD borrows much from the treatment of human lymphoedema, which consists of an “active stage” of reducing the oedema as much as possible, and a “maintenance stage” of using compression garments to stop the oedema (and protein) from building up again. It is also vital that the horse’s primary carers have knowledge about wound care and skin care, so that they can manage their horses’ day to day routine more effectively. Measuring and monitoring form a part of the management routine, to make sure that tissue quality does not worsen.

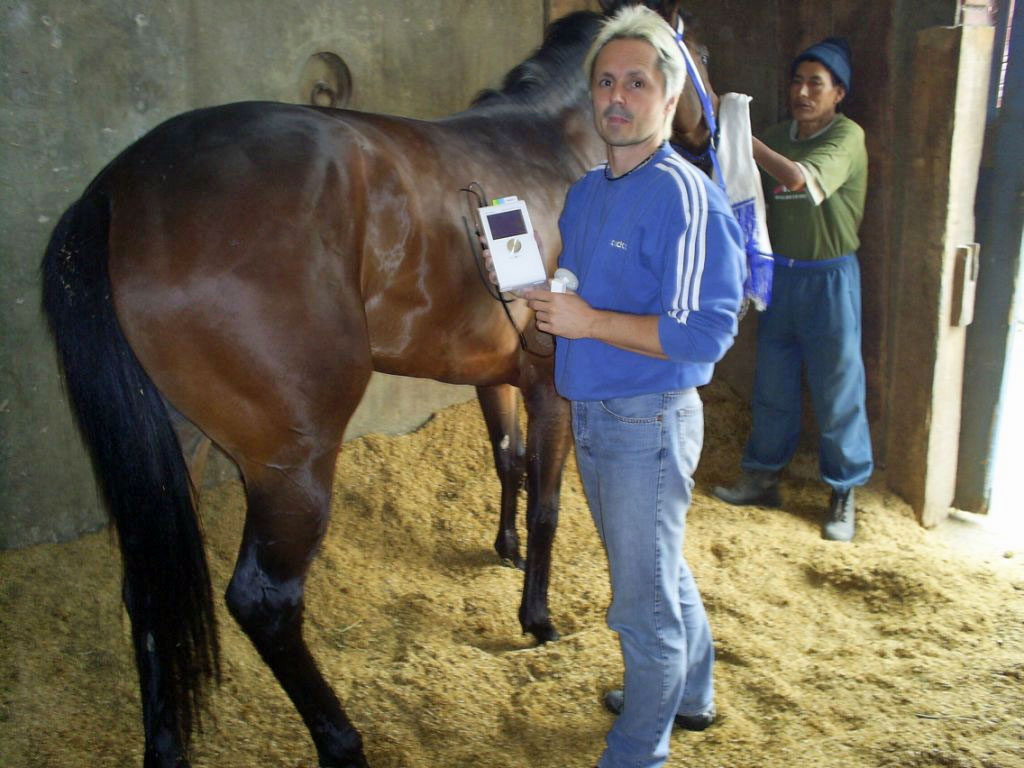

Deep Oscillation Electrostatic Lymphatic Therapy

Bodo Wisst, Physiotherapist in Peru was the first to utilise DEEP OSCILLATION in equine with effective results

As in the treatment of human lymphoedema, the use of Deep Oscillation machine is particularly beneficial to horses suffering from lymphatic disease, especially in cases of lymphoedema caused by scar tissue. It is also very useful in cases where the horse has suffered from repeated infections (usually around the pastern and fetlock joint) as well as horses that have suffered from scarring due to feather mite infestation. Mites are difficult to manage in horses with heavily feathered legs such as Cobs and Shires, where is it common to see thickened scar tissue forming to the lower limbs. Sometimes this damage can be long-standing, and will have become quite fibrotic, but the Deep Oscillation treatment has proven to be effective even in long standing fibroses and scar tissue, sometimes up to 20 years old.

In one instance the author was treating a 27-year-old mare with lymphoedema of the hind leg that started to develop after an ovarian cyst removal operation which was performed when the horse was 8 years old. The scar tissue from the operation covered the area around the iliacal lymph nodes, and through softening the area with intensive treatment with the machine, the oedema resolved due to being able to drain effectively.

The Deep Oscillation machine creates an electrostatic field which "pulls" the tissue layers by attracting and releasing them within the selected frequency ranges between 5Hz and 250Hz. This "shuffling" effect speeds up the healing processes with regard to wounds or injuries, but also reduces oedema and softens protein fibrosis. It is very well tolerated by horses, who often will visibly relax during treatment, and what is especially helpful is that owners can feel the difference themselves within one treatment session.

In conclusion

EMLD is a relatively new therapy but has been used successfully since the 1930’s in human medicine. More research is needed to increase the range of clinical applications of EMLD and the horse community needs to be made aware that there are treatment options available for horses suffering swollen legs as a result of injury or infection. Horses are very receptive to the therapy as it is gentle enough to work around painful wounds or incision sites. It has no adverse side effects and does not contravene any anti-doping legislation, so it allows horses in competitive sport to be treated at any time.

We do, however, need to become much more aware of the equine lymphatic system, not only to support horses lymphatically during their lifetimes, but also to be ready to take preventative measures during the early stages of lymphatic disease in order to avoid the difficulties that occur when the condition has progressed too far.

Rebecka Blenntoft can be contacted at info@equilymph.co.uk

New EquiLymph Website Coming Soon...

References

Berens von Rautenfeld, D., Fedele, C. Lymphologie und Manuelle Lymphdrainage bein Pferd. 2. Auflage, Schlutersche Verlagsgesellscaft (2005)

Berens von Rautenfeld, et al. Manual Lymph Drainage in the Horse for Treatment of the Hind Limb. Part 1- Anatomical Basis and Treatment Concept., Pferdeheilkunde 16 (2000) (Jan-Feb) 30-36.

Brandhorst, B. Manual Lymphatic Drainage after Ventral Midline Laparotomy in Horses. Inaugural Dissertation, The Veterinary University of Hannover, Vet. med. thesis. (2004)

Braun, J. Characterisation of the Lymphatic System of the Equine Integument Using Scanning Electron Microscopy. Inaugural Dissertation, The Veterinary University of Hannover, Vet. med. thesis. (2004)

Fedele, C. and Berens von Rautenfeld, D. Equine MLD for Equine Lymphoedema - Treatment Strategy and Therapist Training, Veterinary Education 19 (1) 26-31 (2007)

Fedele et al. Influence from Cotton Wool Bandages and Elastic Stockings on Lymph Flow in Horses Legs. Pferdeheilkunde 22 (2006) 1 (Jan-Feb) 17-22

Harland, M. Immunohistochemical-Morphometric and Ultrastructural Characterisation of Deep and Superficial Lymph Collectors in the Horse's Hind Limb. Inaugural Dissertation, The Veterinary University of Hannover, Germany, Vet. med. thesis. (2003).

Helling, T. Morphological and Radiological Identification of Lymph Vessels and Effectiveness of Manual Lymph Drainage in the Digital Flexor Tendon of Horses. Inaugural Dissertation, The Veterinary University of Hannover, Vet. med. thesis, (2008).

Risse, M. Concerning Pathogensis of Acute Lymphangitis in the Horse - A Histological, Immunohistological and Transition Electron Microscope Study. Inaugural Dissertation, The Veterinary University of Hannover, Vet, med. thesis, (2004)

Rotting, A. et al Manual Lymph Drainage in the Horse for the Treatment of the Hind Limb. Part 2 - Findings and Treatment in Horses Affected with Chronic Cellulitis", Pferdeheilkunde 16 (2000) (Jan-Feb) 37-44.

All Deep Oscillation References